Urban Renewal - Overview: 1958 - 1962

In the late 1950s, after several turbulent decades, Hooligan Heights was about to undergo a transformation driven by federally sponsored urban renewal. At that time, much of the neighborhood was undeveloped: dirt roads, lack of street sewers, and many dilapidated homes. Some of the afflictions were direct impacts of having been redlined in the 1930s, leaving no opportunities for loans for improvements. The district was about to endure another chaotic era.

As early as the late 1940s, the U.S. Housing and Home Financing Agency (predecessor to the Department Housing and Urban Development) determined that the prevalence of “blight” in urban areas was a detriment to citizens and would hamper investment and positive growth. While “blight” was not clearly defined or quantitatively measured, the department used the generic term to reference “a slum, deteriorated or deteriorating.” To stimulate constructive growth, they gave local governments the power to rehabilitate or seize deteriorating property through eminent domain. Once dwellers were located elsewhere, land could be cleared and then sold to private developers for improvement. This entire process would be heavily subsidized by the federal government. The program started in 1949, and in 1954 it was broadly referred to as “urban renewal.”

Urban renewal was coming to Mishawaka, and the first target would be Hooligan Heights. The classification by the federal government as a hazardous (rated “D”) district in the 1930s had been a sure path to its continued decline. It had been “redlined,” and like other redlined areas across the United States, it was among the first to be subjected to urban renewal. The programs from the past had blocked current or prospective homeowners in certain districts from getting mortgages or loans for improvements. This served as an obstruction for gaining wealth through homeownership and ostensibly led to promoting the cycle of poverty.

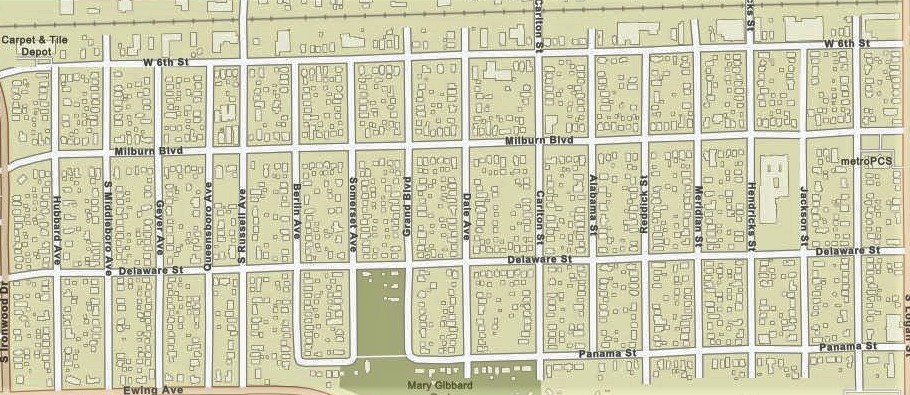

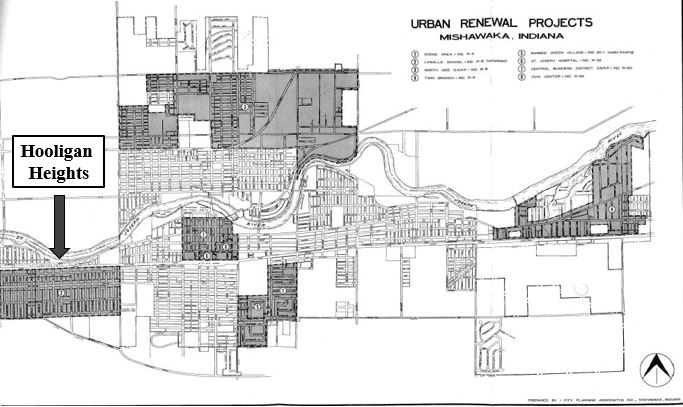

While urban renewal programs were expedited in municipalities throughout Indiana, Mishawaka had a ten-year plan that was one of the largest programs in the state. The city ranked fifth in dollar expenditure and fourth in number of projects, surpassed only by Indianapolis, Gary, and South Bend. In the state of Indiana, over eighty urban renewal projects were seen to completion, and over 10% of those projects were located in Mishawaka. The Hooligan Heights area was first part of the city targeted for revitalization, and it was one of the first programs launched in the entire state of Indiana. This planning process was initiated in 1958, and the project was named “LaSalle School Conservation District.” Its boundaries were Panama/Ewing Street to the south, Logan Street to the east, the railroad tracks to the north, and Ironwood Drive to the west. Unsurprisingly, and mirroring other proposals throughout the United States, the boundaries of the urban renewal project would have the exact same boundaries of the district that had been redlined twenty-two years prior.

In July 1959, the plans that were to impact the neighborhood became more public. At that time, the Mishawaka Redevelopment Commission met publicly with thirty-five civic and business leaders, including representatives from local banks, loan institutions, home builders, lumber yards, hardware stores, and paint supply companies. Also invited were leaders from the Mishawaka Action group and the Southwest Civic Club. Frederick G. Cecchi, director for the urban renewal program, explained that these business firms and civic groups were being asked to “help” people in the LaSalle area rehabilitate their homes. The commission indicated that preliminary plans for conservation work had been completed, and approximately $500,000 in federal funding and grants were to be invested in the area through capital improvements.

While the LaSalle School Conservation District in Hooligan Heights was the first project to be initiated in Mishawaka, it was one of many that would follow. Other areas were located east and south of Dodge Manufacturing (the other redlined district in Mishawaka), parts of Twin Branch, St. Joseph Hospital, and a large swath of what was then the North Side (between Logan Street and Byrkit Avenue south of McKinley Avenue). As was typical in numerous other cities, the majority of the central business district was also targeted for rehabilitation. This would clear the way for a new post office and public library, which both continue to have a large presence in Mishawaka’s downtown today. During this era, almost 1,500 acres were under scrutiny, and as many as 2,000 residential units were demolished. The city displaced hundreds of families and often completely relocated them to other areas of the city.