"Redlining" and its aftermath: 1930s - 1950s

As the reputation of the neighborhood waned, a new federal program was established that promised to bring some semblance of stability to the residents of Hooligan Heights. The Homeowner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) was an appendage of the New Deal, and it was meant to help people purchase homes during challenging financial times. Between 1920 and 1933, authorities had been trying to encourage people to own homes with slogans such as “It’s the patriotic thing to do!” The HOLC program would purchase existing home mortgages that were about to go into foreclosure. They would then issue new mortgages, with low interest, to be paid out over 15 years and amortized. The risk assessment on the mortgages was conducted by local real estate agents who made appraisals.

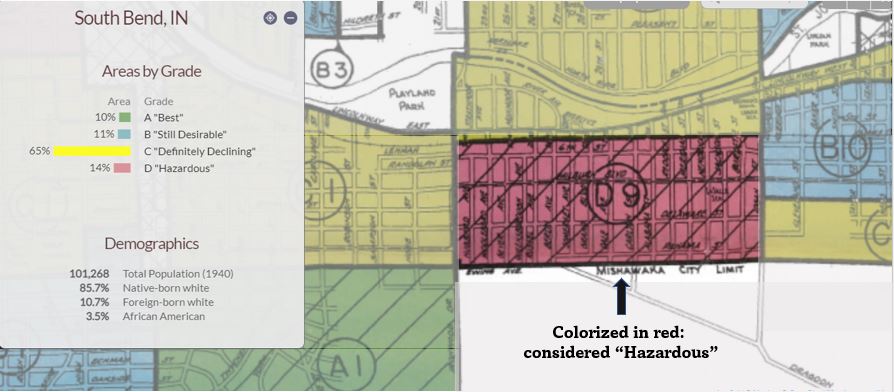

In 1934, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was established, issuing bank mortgages and covering a sizable portion of the cost. However, before they would do this, they needed to ensure that a home was a suitable risk. The FHA allowed the HOLC to create “residential security maps” to assess the level of risk in neighborhoods in many cities in the U.S., including Mishawaka. HOLC evaluators collaborated with loan officers, city officials, and realtors to classify communities by a rating of A, B, C, or D, according to perceived risk. Included in these assessments were age and condition of housing, amenities, economic class, employment status of residents, and racial and ethnic composition. The classifications were outlined on maps, with A in green (Best), B in blue (Still Desirable), C in yellow (Definitely Declining) and D in red (Hazardous). Homes in the green areas were considered an excellent risk and good candidates for a mortgage, while neighborhoods in red (Hazardous) were of the highest risk and not recommended for a guaranteed mortgage. Neighborhoods dominated by minorities were always given the lowest and riskiest classification: red. If structures were in less than pristine condition or if dominated by subjectively defined “lower class occupants,” it also could relegate the neighborhood to a red designation. The categorization was often simply justified in the paperwork as due to the “quality of the inhabitants.” This practice is referred to today as “redlining.” Lack of loans for buying these properties or making improvements or repairs made it difficult for these neighborhoods to attract and keep residents. Many urban historians point to this federal legislation and its intractable aftermath as the main reason for the decline of urban areas in the middle of the twentieth century.

While HOLC generally only evaluated larger cities (50,000+), Mishawaka’s proximity to South Bend would drive the federal agency to classify both cities’ neighborhoods in June of 1937. In the evaluations, some neighborhoods, such as the West End, The Oaks, and Merrifield, were considered good risks. Most others received a mid-grade rating, with a chance of deterioration. Only two areas in Mishawaka received the worst classification: the hazardous D-rating. One was the area just south of Dodge Manufacturing, and the other one was the neighborhood still formally known as “Floral Park.” Hooligan Heights had been redlined.

Floral Park (Hooligan Heights) is "redlined" by Homeowner's Loan Corporation

As the city of Mishawaka was 99.8% white at the time, the authorities did not redline areas due to racial composition. The assessors were clear about this in the paperwork, indicating racial homogeneity. However, the biggest concern around Dodge Manufacturing was the “infiltration” of Belgians and Italians, with the assumption that this encroachment would bring about the demise of the area. While Hooligan Heights was first settled with a sprinkling of Belgians, by 1937 no dominant foreign ethnicities were present in the area. On the evaluation, the reviewer noted under descriptions about the terrain: “Level. Known as Floral Park. Sparsely settled with small, dilapidated shacks.” This authority did not see the “beautiful home sites at the foot of the picturesque Mishawaka Hills,” as developers had so artfully described a mere 25 years prior.

In the official federal report on Hooligan Heights, the inspector went on to report that no favorable influences existed in the area. Additionally, the assessor noted that detrimental influences included the type of construction and the inhabitants, which were made up of mostly a laboring lower class. While most of the homes were less than 20 years old, inspectors saw significant disrepair. The effects of the Depression loomed large, and a D-rating was only going to exacerbate financial woes. Without an ability to obtain secured mortgages or loans for renovations or property improvements, the stage was set for rapid decline. Hooligan Heights would be embarking on a downward spiral, the same path of decline for redlined neighborhoods throughout the United States.

Residents of the area were not immune to understanding how they were viewed by local leaders and Mishawakans who lived in other sections of the city. They often voiced their frustration with what they perceived as unfairness by the city council, believing they were targeted due to their economic status. In early 1945, when the city decided to close ten of the 30 New York Central railroad crossings, the citizens of Floral Park erupted. The New York Central Railroad ran through the north side of the neighborhood, and closings would create difficulty in getting quickly to Lincolnway and other parts of the city. The closing of the Dale Avenue crossing caused the most consternation, leading to threats of the secession of Floral Park from the city of Mishawaka. At the public hearing, a resident angrily suggested that the city council was purposefully trying to “bottle up” the southwest part of the city since they lived in the “Hooligan Heights” district. Later that year, a resident wrote an editorial to the South Bend Tribune, bemoaning the closings that effectively blocked the southwest side from the city’s main artery, Lincolnway, as they live on the “wrong side of the tracks.” The letter was proudly signed: “Hooligan Heights Resident.” Shortly after this, the name “Floral Park” became used less frequently, and it eventually drifted into obscurity.

By the late 1940s and into the 1950s, residents continued to be frustrated by the reputation and economic decline of the area. In 1949, the Southwest Civic Club was formed to advocate for the neighborhood and to work with the city to get better amenities on the southwest side. In particular, the group was interested in developing a park with playground equipment. After raising money and lobbying the city, their efforts were successful. South West Park (the future Mary Gibbard Park) opened in 1951, much to the excitement of the community. However, the new park was not the silver bullet that would bring prosperity to the district. Many homes in the area were dilapidated, and some were beyond repair. Many residents were living in poverty.

The story of Hooligan Heights was one that was typical across America, particularly in places that had been redlined. The federal government took notice, as blight was raging in cities everywhere from fallout from the New Deal housing programs of the 1930s. They had a plan. They were about to give local governments the power to rehabilitate or seize deteriorating property through eminent domain. Once dwellers were located elsewhere, land could be cleared and then be sold to private developers for improvement. This entire process would be heavily subsidized by the federal government. The program started in 1949, and in 1954 it was broadly referenced as “urban renewal.”

Urban renewal was coming to Mishawaka.

While the post-Depression struggles of Hooligan Heights appear typical for an underclass neighborhood in a small city, what would come next was unthinkable. Cities throughout America are still trying to unwind and rectify the damage from urban renewal programs of the 1950s – 1960s. These programs often decimated communities and abandoned the most impoverished citizens. Neighborhoods in Mishawaka would not be unscathed; to the chagrin of despondent residents, much of Hooligan Heights was about to be obliterated.