Urban Renewal - Upgrades and Improvements: 1960-1961

When the next grant from the federal government arrived, it was slated for infrastructure and capital improvements to the area. Prior to 1960, the roads in Hooligan Heights were unpaved without sewers or gutters (with the exception of Milburn Boulevard). Long-time and former residents have memories of the oil trucks rumbling through the streets in the summer, spraying down gravel to keep the dust to a minimum. Most of the north/south extension streets that ran south of Panama were abandoned during the renewal process (Burdette, Meridian, Reddick, Alabama, Dale), but remnants of them exist today. Several homes on these southerly extensions still face the original dirt roads. An inspection of these extensions can help an observer understand the landscape of Hooligan Heights before 1960, as in the recent photo of Meridian Street south of Panama (pictured). After the completion of the renewal project, residents would have newly paved streets, sewers, gutters, and sidewalks. They also would get additional new fire boxes and experience zoning changes that would relegate the business district to the main thoroughfares and the industrial district to Sixth Street. Developers arrived on the scene, building cottages for new residents who would take the place of the ones who could no longer afford to live there.

In August 1960, the Reed Construction Company, 202 ½ N. Main Street, began work on some of the key infrastructure improvements. Reed had been awarded the contract as the lowest bidder on new sewers, sidewalks, and curbs. The company would lay 1.5 miles of sewers, as well as 33,275 square feet of new sidewalk and 3,594 lineal feet of new curbing. The first sewer was installed at Alabama and Sixth Streets, as the first new sewers were to run under Sixth Street from Alabama to Dale and from Meridian to Hendricks. However, the largest sewer was a relief sewer, running the entire length of Delaware Street, 16 ½ blocks. The company was given 170 days to complete the work. In addition to sewers, sidewalks, and curbs, 6 ½ miles of streets would be paved, most of them for the first time.

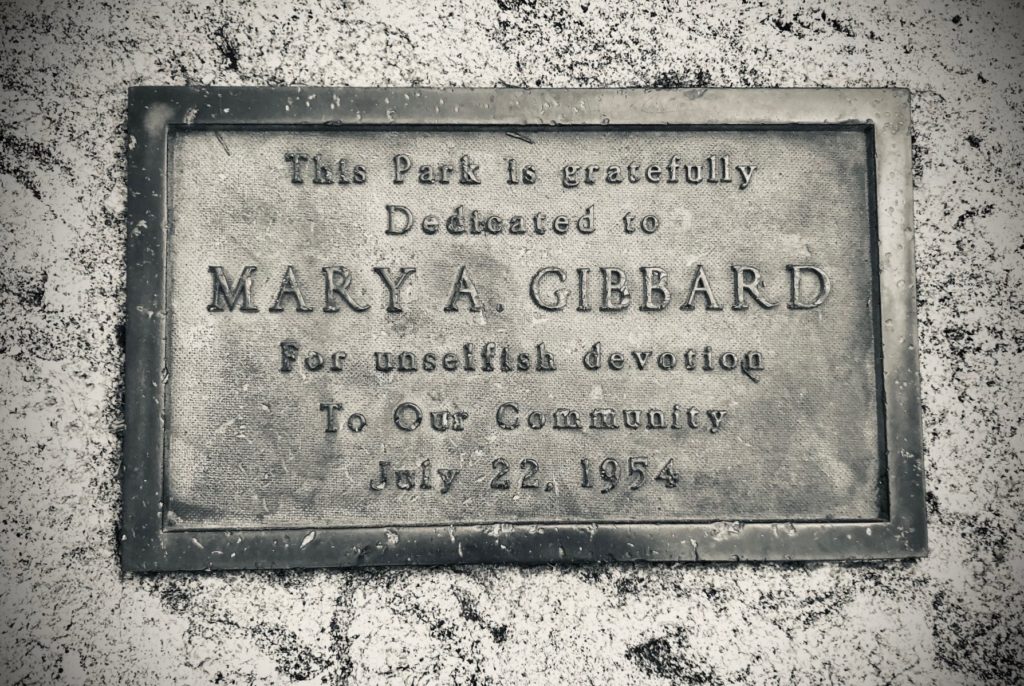

One of the most significant improvements to the area was the revitalization of the local park. Mary Gibbard Park, which was formerly called South West Park, had only christened its new name six years prior. Mary Gibbard had been the principal of LaSalle School for twenty-five years, until her retirement in 1952. Additionally, she was also a prominent civic leader on several levels. She served at the local, state, and national level for Altrusa International, a world-wide organization of executives and professional leaders who are dedicated to improving their communities. She was a graduate of the University of Chicago and received a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1933. When the park was dedicated in 1954, the celebration included a live band and square dancing in the park. Mary Gibbard passed away in 1956, so she would never see the vast improvements and upgrades in the park that bore her name.

To accommodate the needs of existing and new residents, the park would expand to six acres, doubling in size. The redevelopment commission also promised upgrades to the surrounding streets, replacing and rebuilding curbs and sidewalks, installation of streetlights, improvements to the storm sewers, and the development of playgrounds. Streets around the park, Somerset and Grand, were paved for the first time and widened to accommodate diagonal parking. However, the most significant enhancement to Mary Gibbard Park was the installation of a brand-new aluminum pool, which became an important focal point for area residents. Constructed in early 1961, it was the first city-operated public pool in Mishawaka. It was L-shaped, divided into a 35’x72’ section that was 3-5 feet deep and a 35’x40’ diving area. Surrounding the pool was a 20’ concrete apron and a brand new 50’x32’ bath house, which housed dressing rooms, toilets, showers, a storage room, and a checking room. From the 1960s-2010s, the pool was the place where neighbors would meet in the summer to cool down and where many local children learned how to swim. Even today, former and current residents wax nostalgic about their fond memories at the Mary Gibbard Pool.

After the opening of the pool in July 1961, the redevelopment commission launched into a beautification program for the LaSalle area. The Southwest Civic Club wholeheartedly embraced the project, urging residents to do their part clean up their property and to keep their lots trimmed and tidy. This effort was to ensure that all the labor and capital that had been invested in the area was not for naught; the Civic Club was invested in ensuring that the neighborhood remained “as nice as it is now.” They offered advice and assistance to all residents, especially those who had disabilities and may have had challenges restoring and beautifying their dwellings and yards.

The final phase of renewal for the LaSalle area started in the late summer of 1961. At that point, all 117 parcels that had been acquired were ready to be sold by the redevelopment commission. The sale of these lots was touted as “one of the first to be held in Indiana as a result of the federally financed program for the removal of slum and blight conditions.” Bids on 52 of the lots opened on August 28, 1961, in the redevelopment office at City Hall. These parcels had already been cleared of the “blighted” dwellings, while the remaining lots were not yet available. Because of the complicated steps that were required to purchase federally owned property, two seminars were held to acquaint prospective bidders with the necessary procedures. All lots were FHA approved, and they sold for about $23 per front foot. Vannoni then indicated that the LaSalle neighborhood was “an essentially renovated area.”

Mishawaka city officials and the redevelopment commission were anxious to call the LaSalle School Conservation Project a success. In 1961, Joseph Canfield, mayor of Mishawaka, testified in front of the Federal Housing subcommittee on behalf of the American Municipal Association. He was touting Mishawaka’s urban renewal accomplishments in the LaSalle district. He indicated that the city was able to remove blight and provide safe, sound, and decent housing to residents due to financial resources, sound leadership, and collaboration with the federal government. In his testimony, however, he indicated that he was clearly aware of the fact that the FHA’s practices of not insuring mortgages or renovations (redlining) had brought about the ultimate decline of the neighborhood. Interestingly, Mayor Canfield candidly told the subcommittee that the neighborhood had been aptly dubbed “Hooligan Heights” due to its deterioration and lack of facilities. He then indicated that, moving forward, the renewed “fine residential neighborhood” would be renamed the “LaSalle School area.” Unbeknownst to him, the name Hooligan Heights would never be completely retired, and it would be fully reactivated within a generation.

As early as the fall of that same year, residents were already pushing back against the establishment of a meat distributing center at Sixth Street and Somerset Avenue. After all the work that had been completed to improve the appearance of the community, the city was once again dismissive of the area, allowing some of the least desirable industries to position themselves in the middle of the recently upgraded residential district.