Immigration and Racially Restrictive Covenants: 1900s - 1960s

Not only did Mishawaka’s population explode between 1900 and 1930, but the number of people in South Bend and the surrounding areas also grew exponentially. The drivers of growth in local population were due to a number of factors. While immigration had been severely restricted by the Immigration Act of 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act), people who had immigrated right after the turn of the century tended to have large families, creating a population boom in the 1910s and 1920s. The newest wave of immigrants to Mishawaka during that timeframe was comprised of Belgians and Italians. Between 1900 and 1930, the Flemish population alone grew from less than 300 to well over 2,300. Additionally, Mishawaka’s Italian population consisted of less 10 people in 1900, but it had grown to almost 1,000 by 1930.

Concurrent with waves of European immigration and their fecundity, another phenomenon was taking place during that time. It was called the “Great Migration,” when approximately six million Black people moved from the American South to northern, midwestern, and western states from the 1910s until the 1970s. Multiple driving forces were at play in this movement. In the South, new agricultural tools and mechanization brought about the obsolescence of manual work, making it difficult to find employment. Legal barriers obstructed Black people from choosing certain vocations and created barriers to social status and property ownership. Additionally, racial violence was on the rise. The Black population initially came to industrial cities outside the South to pursue economic and educational opportunities and to obtain freedom from the oppression of Jim Crow laws. When the war effort escalated in 1917, more able-bodied men were sent off to Europe, leaving their industrial jobs vacant. With immigration from Europe also in decline, a labor shortage persisted. All of this afforded the opportunity for the Black population to move to other places and become the labor supply in non-agricultural industries.

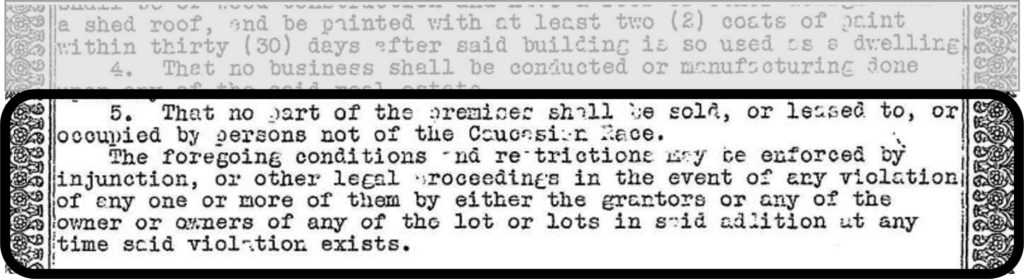

Many of the communities that were seeing growth due to the Great Migration were not particularly comfortable with the prospect of living in an integrated area. At one time, cities in the United States were allowed to enforce segregation ordinances. When enforcement of these ordinances was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1917, property owners had to find another way to ensure that they would never have to live near African Americans or other minority groups that were perceived as undesirable. To do this, developers and real estate boards established racial restrictions on tracts of land. Additionally, property owners could establish racially restrictive covenants on their property or their block. These covenants were tied to property deeds or plat maps, and they legally prohibited an owner from selling to a specific minority group. These contracts would disallow the signer and all future property owners from selling to whomever they wanted. If an owner ignored the restriction, they could be sued and held financially liable. Entire neighborhoods were restricting the sales of homes to African Americans by the mid-1920s, and this continued for decades. Mishawaka was no exception.

Like other industrial areas, St. Joseph County would witness the growth of the Black population firsthand. However, not all areas were inclined to integrate these newcomers into the community. While some city neighborhoods and towns throughout St. Joseph County may have quietly desired racial homogeneity, many were unabashedly discriminatory. The brand-new subdivisions on the west side of Mishawaka fit into the latter category.

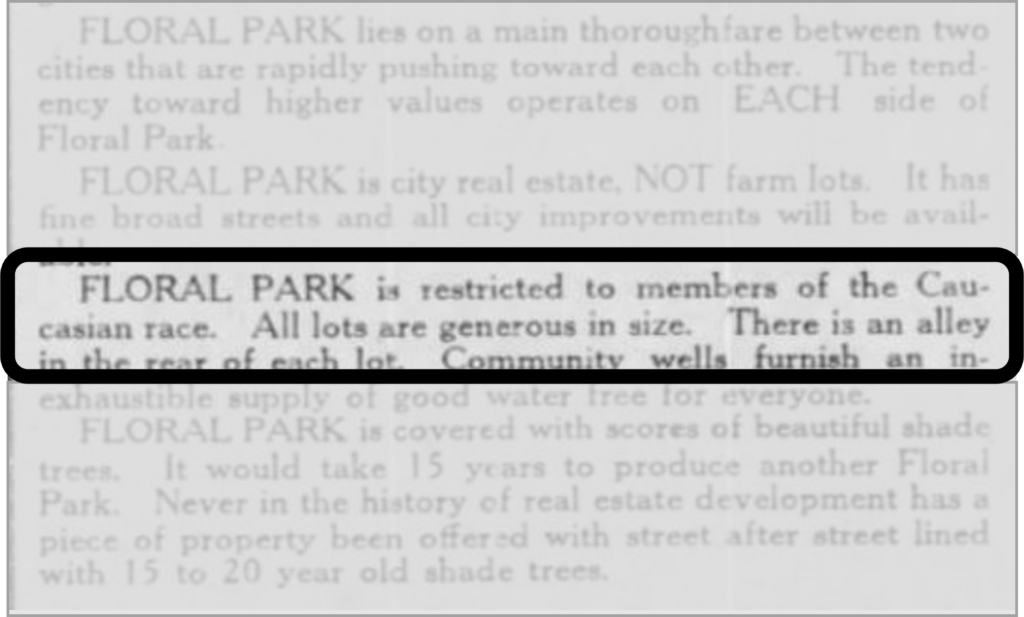

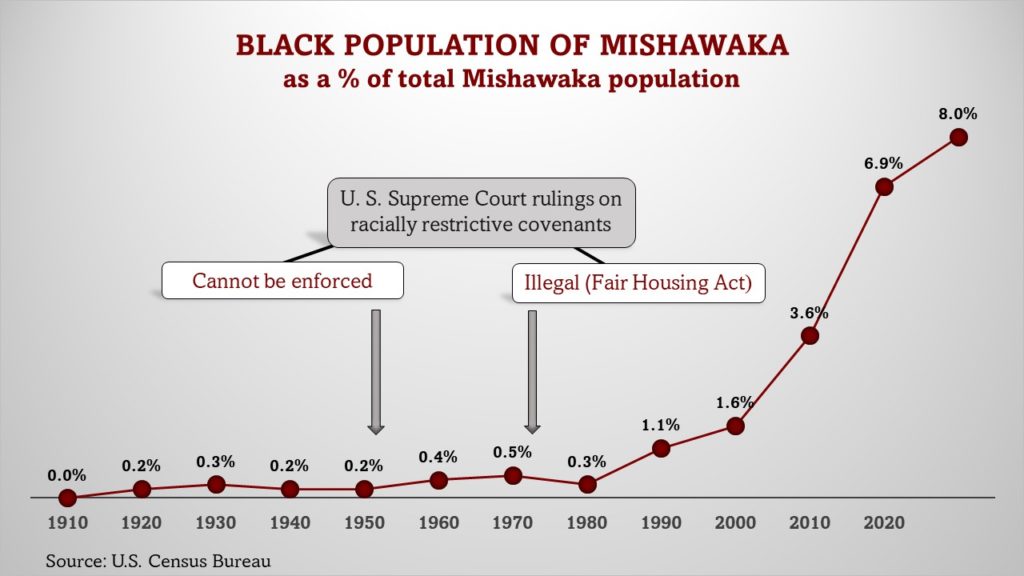

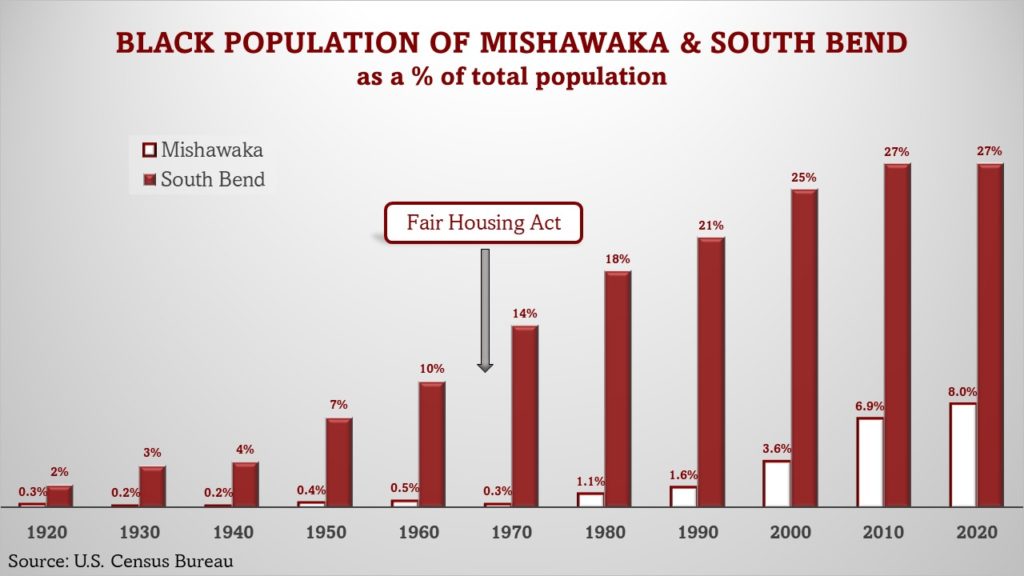

In the Floral Park area, new owners might be legally bound to spend a certain dollar amount on their new home. However, other publicized restrictions were vague. Developers indicated that they would only sell to the “best class of buyers…and no lots would be sold to undesirable people.” While this language is subjective, by late 1920, the public advertisements were completely overt: Floral Park was “restricted to members of the Caucasian race.” These rules legally obstructed anyone who was not Caucasian from living in the Floral Park area, and remnants of these policies lasted for years. While the Supreme Court deemed these covenants unenforceable in 1948, many of them were still in use privately until 1968. This is when they became explicitly illegal through the Fair Housing Act. In the latter part of the twentieth century, newcomers and younger people were often befuddled over the invisible color line that was seemingly drawn down Ironwood Drive. Today, enforcement of these inequitable policies is illegal, and the area is open to all. However, we still can see some of the vestiges of the past when we compare the size of the Black populations of South Bend and Mishawaka today.